The Rhodesian Dog Whistle: Part I – Introduction to the Claims and a Rebuttal Framework

Originally published on A Plague on Both Houses where you can also access an audio version of this article.

This essay is Part I of an eight-part rebuttal of claims made by Lies are Unbekoming in his defence of colonial Rhodesia. You can read the web archive version of that piece here:

https://web.archive.org/web/20251213170310/https://unbekoming.substack.com/p/the-rhodesia-myth

For an explanation of why I am taking the time to rebut that Unbekoming piece, please read my Introduction to the Introduction.

That piece is important because it clearly sets out my position on Rhodesia, the Rhodesia Myth I am challenging, and the importance of challenging the myth.

In blunt terms, my position is that Rhodesia was a racist colonial shithole, and I will be attempting to prove that conclusively.

Unbekoming, in a defence of colonial Rhodesia, promotes the phantasy that Rhodesia was a beacon of light in the otherwise grim annals of colonial history. This phantasy is what I call ‘The Rhodesia Myth.”

In this piece I will set out my stall by:

- Providing a distillation of the Rhodesia story to set the scene for the claims I am rebutting and the framework of the rebuttal.

- Outlining the five major claims made by Unbekoming in his defence of colonial Rhodesia, explaining the framework for my rebuttal of those claims, and pointing the reader to the following parts where each claim will be discussed.

- Discussing material omissions, contradictions, and other problems with the claims as a prelude to the essays which follow this introduction.

- Explaining the racial terms used in discussing the history of Rhodesia

A distillation of the Rhodesia origin story

Animated by legendary tales “of quartz reefs, miles in extent, bearing visible gold”, which reputedly lay beneath the ground in Zimbabwe, a group of European pioneers occupied Mashonaland on 12th September 1890, and claimed it for “Queen and country”. Sponsored by the world’s most notorious colonial oligarch at that time, Cecil John Rhodes, they never doubted “that a few months of simple quarrying would make them rich beyond the dreams of avarice.”[i]

Rhodes’ British South Africa Company (BSAC), a Royal Charter company designed to provide an overtly commercial route to colonising a territory without incurring government expense, began administering the territory and its people, and annexing land. Not only was it a violation of Natural Law, it was illegal even under colonial legal frameworks which were designed to legitimise such violations. This first violation was followed by a war of conquest in 1893, and the violent suppression of uprisings of the indigenous people in 1896-7.

Squeezed off the land and cruelly coerced into the settlers’ cash economy as cheap labour, the indigenous people were gradually deprived of their traditional pastoral way of life. Denied land, employment, and educational opportunities in the imposed modern economy, the indigenous people were left to languish on the periphery of White society. Left in this limbo state without adequate land for self-subsistence, the vast majority struggled to maintain a foothold in cramped rural areas while serving as a cheap labour pool doing menial jobs on White-owned farms, as well as in mines and factories, and as domestic helpers for the most meagre of wages.

With vast wealth, income and educational disparities baked into the racialised socio-economic system, the White ruling minority, representing roughly 5% of the total population, played one final cruel joke on the Black majority. They constructed a “merit-based” voting franchise whose qualifications were based on wealth, income and education. The misnamed ‘franchise’ was out of the reach of virtually the entire Black population.

Faced with a rising tide of Black resentment in the post-war period, and emboldened by a sense of entitlement, the White minority chose to contain the aspirations of the Black majority for equality, and to preserve White privileges built up over 75 years. With their backs to the wall, the settlers adopted a laager mentality and made a last stand, as they had done in the occupation and conquest of the land and its people in the last decade of the 19th century. Right up until 1960, all seats in the House were guaranteed to go to White candidates. In 1962, the number of seats increased, but 76% of the seats were guaranteed to end up in the hands of White candidates representing the interests of a minority of 250,000 White Rhodesians – under 5% of the total population of 5.4 million people. Conditioned to see the world only in Black and White, they had become, in the words of their own Prime Minister in 1938, “an island of white in a sea of black” – completely incapable of imagining a society not divided by skin colour.

The five major claims made by Unbekoming in defence of colonial Rhodesia

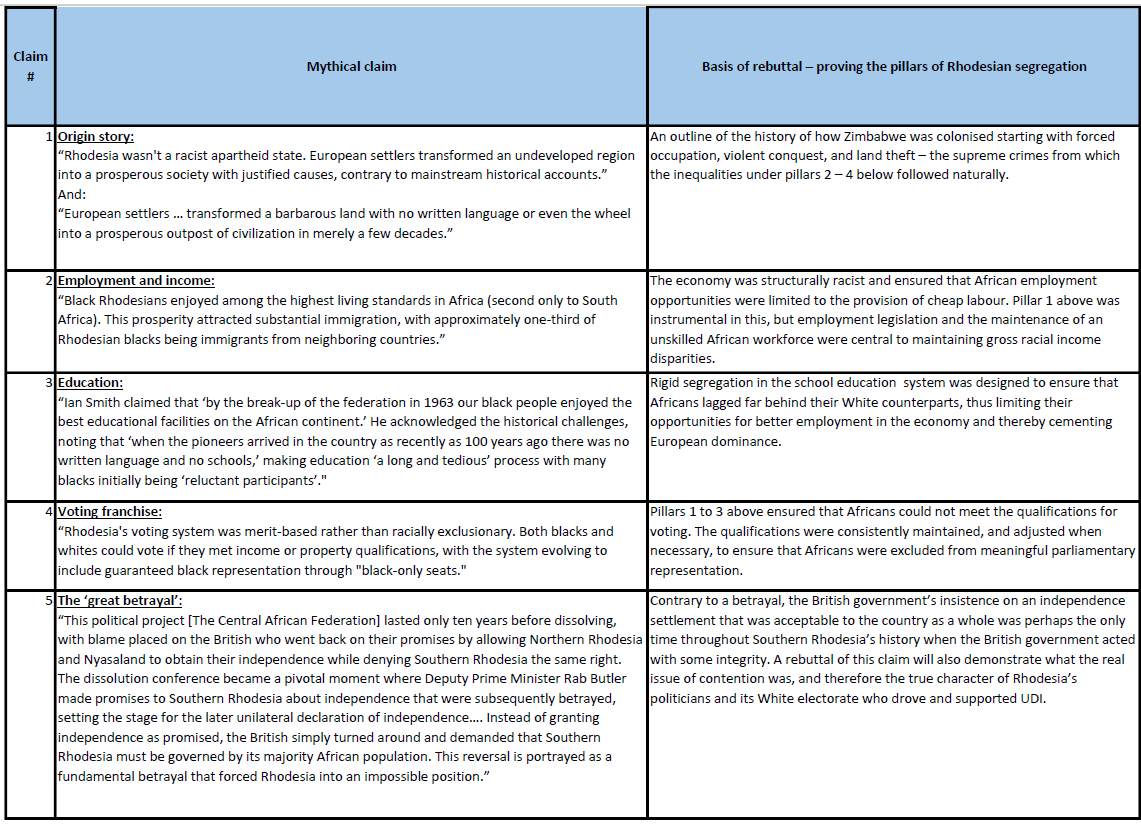

There are five material claims made by Unbekoming. I will now lay out each claim, together with the approach for rebutting it, and a reference to the subsequent essay that deals in detail with the claim.

The order of the claims, and the rebuttal thereof, is important. Each claim made by Unbekoming will be matched to a pillar of Rhodesian segregation that illustrates why the claim is false. There is therefore a logical sequence to the claims and the related rebuttal, starting with the origin story, and then moving through each pillar of segregation, until we arrive at the final pillar – the voting franchise – which is wholly dependent on the preceding pillars for its survival. The last claim of a ‘great betrayal’ is not related to a central pillar of segregation, but a rebuttal of it is worth engaging in since it opens up a discussion of a pivotal moment in Rhodesian history that gives more context to the regime’s fight for survival in its final years.

Claim # 1 – the origin story (or absence of an origin story)

Claim:

“Rhodesia wasn’t a racist apartheid state. European settlers transformed an undeveloped region into a prosperous society with justified causes, contrary to mainstream historical accounts.”

And:

“European settlers … transformed a barbarous land with no written language or even the wheel into a prosperous outpost of civilization in merely a few decades.”

Both statements can be grouped as one claim in that they articulate the idea that the settlers arrived and performed miraculous and beneficial feats of development and transformation. The claim even states they had good reasons for doing the transforming, although these reasons are not expounded upon in any detail at all.

The rebuttal:

The narrative presented by Unbekoming is completely devoid of an origin story. The above claims constitute the entirety of the narrative of the settlers’ arrival and first encounters with the original inhabitants. The absence of a proper account of the settlers’ first encounter with the indigenous inhabitants is of course deeply problematic in the context of colonial history.

The rebuttal approach, though by necessity lengthy, is straightforward. I will lay out the facts and information that support a narrative of forced occupation, violent conquest, and land theft by the European settlers. It’s a story with which scholars of colonial history will be painfully familiar, but nevertheless germane to an assessment of the Natural Law violations that occurred, and a proper deconstruction of the facile and grossly misleading claims above.

Using the Nuremberg Trials analogy, this is an accounting of the ‘supreme crime’ from which all the others below – described in the rebuttal of claims 2 to 4 – flow. In laying out the origin story in sufficient detail, I hope to show, in Professor Reginald Austin’s words, that: “Southern Rhodesia was thus one of the very few cases in Africa of colonial acquisition by undisguised conquest… Rhodes, the BSAC and the settlers, granted permission only to exploit minerals by the king [Lobengula], manipulated the situation and the British Government into a violent confrontation in order to take complete control.”[ii]

The rebuttal of claim #1 with a detailed origin story takes place in the following essays:

Part II – Concessions as Fig Leaves for Occupation

Part III – Conquest and Uprisings

Part IV – Rhodes and Rhodesians: A Character Portrait

Part V – “Who Gave You This Land?”

Claim # 2 – Employment opportunities and income

Claim:

“Black Rhodesians enjoyed among the highest living standards in Africa (second only to South Africa). This prosperity attracted substantial immigration, with approximately one-third of Rhodesian blacks being immigrants from neighboring countries.”

The rebuttal:

It is very rare for a claim to qualify as both devious and stupid, and yet this claim achieves both. It is devious because it avoids the real issue by inviting you to compare the living standard of Africans in Rhodesia with that of Africans in other territories. Not only is such a comparison completely irrelevant to a proof that Rhodesia was discriminatory, but it avoids an examination of structural inequalities within Rhodesia itself. And in that sense it is obviously stupid in its premise – namely that it regards the racial disparities within Rhodesia as irrelevant to an assessment of Rhodesian segregation. I will go into more detail on this below under the heading – Material omissions, contradictions, and other problems with the claims.

As for the rebuttal approach, a racially segregated society in which one group dominates another tends to produce marked disparities in employment opportunities and income in order to serve the interests of the dominant group responsible for erecting and upholding the segregationist architecture. My objective will be to demonstrate that the ‘supreme crime’ of land annexation and land impoverishment described in the rebuttal of claim # 1 led inexorably to the creation of a cheap African labour pool in the service of White Rhodesian economic interests. This will be done in the following essays:

Part V – “Who Gave You This Land?”

Part VI – Employment, Income and Education

Proving gross income and wealth disparities, and their relationship to a racially segregated society, is also foundational to rebutting claim # 4, which is related to the voting franchise.

Claim # 3 – Education

“Ian Smith claimed that ‘by the break-up of the federation in 1963 our black people enjoyed the best educational facilities on the African continent.’ He acknowledged the historical challenges, noting that ‘when the pioneers arrived in the country as recently as 100 years ago there was no written language and no schools,’ making education ‘a long and tedious’ process with many blacks initially being ‘reluctant participants’.”

The rebuttal:

This claim is similar to claim #2 relating to employment and income in that it invites you to compare Rhodesian African educational opportunities with African educational opportunities outside Rhodesia. And, for the same reason I gave in the rebuttal approach for claim #2, it is entirely irrelevant to proving whether Rhodesia was a racist apartheid state.

The rebuttal will simply focus on demonstrating vast racial disparities in education within Rhodesian society, and that government policies were wholly responsible for these disparities. As a result, they were indicative of racist policies in education. This will be done in the following essay:

Part VI – Employment, Income and Education

As with claim #2, proving that gross educational disparities were caused by state education policies is foundational to rebutting claim # 4, related to the voting franchise.

Claim # 4 – The voting franchise

“Rhodesia’s voting system was merit-based rather than racially exclusionary. Both blacks and whites could vote if they met income or property qualifications, with the system evolving to include guaranteed black representation through “black-only seats.”

The rebuttal:

Those who adhere to the legalistic argument that Rhodesia’s voting system was not “racially exclusionary” when there is ample evidence to demonstrate that the voting qualifications were constructed specifically to exclude an already economically and educationally marginalised group, are being disingenuous. I have used the word “disingenuous” in the interests of maintaining an appropriate degree of decorum, as well as to give those making the claim some benefit of the doubt. However, those making the claim with knowledge of the design and effect of the ‘franchise’ do not deserve this level of courtesy.

An analysis of the voting franchise policy, from its inception right through to 1978, should conclusively demonstrate that it was the final nail in the coffin of African economic and political advancement.

The rebuttal of claims 1 – 3 is foundational to rebutting the voting franchise claim since deliberate land, employment and educational impoverishment were the cornerstones of the racially exclusionary voting franchise. This rebuttal will be done in the following essay:

Part VII – The Voting Franchise

Claim # 5 – The ‘great betrayal’

This claim relates to the circumstances in which the colony of Southern Rhodesia rebelled against the Crown in November 1965 by unilaterally declaring its independence from Britain. The claim is:

“This political project [The Central African Federation] lasted only ten years before dissolving, with blame placed on the British who went back on their promises by allowing Northern Rhodesia and Nyasaland to obtain their independence while denying Southern Rhodesia the same right. The dissolution conference became a pivotal moment where Deputy Prime Minister Rab Butler made promises to Southern Rhodesia about independence that were subsequently betrayed, setting the stage for the later unilateral declaration of independence…. Instead of granting independence as promised, the British simply turned around and demanded that Southern Rhodesia must be governed by its majority African population. This reversal is portrayed as a fundamental betrayal that forced Rhodesia into an impossible position.”

The rebuttal:

This claim, though not central to proving the existence of an apartheid system in Rhodesia, is a convenient segue to a discussion of a pivotal event in the history of Rhodesia. The Unilateral Declaration of Independence (UDI) was effectively the settlers’ last stand. An examination of this claim will lay bare the character of the person most responsible for propagating the claim – Rhodesia’s Prime Minister at the time, Ian Smith – and the White Rhodesian electorate who supported him until the very end. Crucially, in explaining the real issue of contention during this period of history, I will try to show that, contrary to a betrayal, it was perhaps the only time in Rhodesia’s entire history when the British government acted with some integrity in its insistence on an independence settlement that was acceptable to the country as a whole, and not merely to the White ruling minority.

If the above framework is clear, you can skip the table below and proceed to the next heading.

If you’d like to consolidate your understanding of the claim/rebuttal framework, the above narrative has been condensed into the table below to give as succinct a summary as possible:

Material omissions, contradictions, and other problems with the claims

Let’s start with the most material omission in the Unbekoming narrative.

It is important to stress that there is no acknowledgement in the Unbekoming piece of the primary, and causative, events of forced occupation, conquest, and land theft. To borrow Nuremberg Trial terminology, these events are analogous to the supreme crime from which all the other evils flow. This omission is equivalent to describing the Iraq war of 2003 by saying: “War broke out between Iraq and the US, and the latter was victorious.” Neglecting to mention that the US invaded Iraq illegally, and neglecting to interrogate the deceptions perpetrated prior to the invasion, would represent material omissions of fact.

Related to this omission, we are told that the settlers had “justified causes” for undertaking their miraculous transformation of an “undeveloped region”. There is no explanation of these “justified causes”. No half-decent historian, even those sympathetic to Rhodesia, would attempt to deny that an absolute imperative driving the colonial occupation in Rhodesia was gold, and controlling the land that contained the gold. The entity that sponsored the occupation of Mashonaland in 1890 and went on to administer Rhodesia until 1923 was effectively a consortium of shareholders who represented a syndicate of mining interests that Rhodes had consolidated in order to form the British South Africa Company. The Royal Charter, which effectively authorised the Company’s occupation, was granted on the strength of a mining concession possessed by the Company. These facts and their significance will be developed more fully in Part II, Part III, and Part IV.

Gold was not the only imperative driving colonial conquest in the region. Rhodes was animated by his vision of a British empire stretching from the Cape to Cairo, and with the infamous Scramble for Africa well underway, securing territory north of the Limpopo was uppermost in the minds of imperial planners, including Rhodes. But Rhodes was particularly obsessed with the land north of the Limpopo because he believed it was the second Eldorado, and that exploiting it would go a long way towards financing the costly business of empire building.

Let’s now move on to some contradictions, some of which have been alluded to in the rebuttal framework above. Making the claim that: “Black Rhodesians enjoyed among the highest living standards in Africa (second only to South Africa)”, while advancing the hypothesis that “Rhodesia wasn’t a racist apartheid state”, is itself a racist claim, and therefore contradicts the denial of Rhodesia being racist. This is because the claim is concerned with a comparison of Black Rhodesian living standards to that of other Africans outside the territory. It avoids an analysis of the vast disparities between Black and White living standards that actually existed within Rhodesia, which is the only comparison that matters in an analysis of structural racism within Rhodesia. In crude terms, those making the claim are effectively saying: “Rhodesia’s Helots were better off than other colonial Helots; ergo Rhodesia was not oppressing its Helots.”

The claim made by Unbekoming in relation to education is structured in exactly the same way, and is therefore equally ludicrous.

The claim regarding African living standards in the Unbekoming piece is made under the heading “African Living Standards Under White Rule”, which again presents a contradiction when trying to argue that Rhodesia was not racist. One ought to at least explore how the system could possibly have been free from racial discrimination if the 95% majority Black population were “under White rule” of a colonially imposed 5% minority. A very cursory investigation would reveal that the Black majority did not voluntarily place themselves under white minority rule in a democratic system.

The education claim states: “Ian Smith claimed that ‘by the break-up of the federation in 1963 our black people enjoyed the best educational facilities on the African continent’”, but then goes on to assert that “many blacks [were] ‘reluctant participants’”. We thus see a contradiction within the claim – on the one hand, Smith claimed the “best” educational facilities but, on the other hand, there was a failure to achieve good educational standards, with blame being assigned to the pupils themselves.

This blaming and shaming of the pupils was repeated by Smith after independence when the Zimbabwean government achieved in 15 years something that had eluded White Rhodesian governments for 90 years – one of the highest literacy rates in Africa. Despite 90 years of failure in African education, Smith then astoundingly took credit for Zimbabwe’s success. Unbekoming shamelessly repeats this claim: “Smith emphasized that the ‘tremendous impetus to education’ after 1980 was only possible “because of the foundation and infrastructure they inherited” from the white government.”

I have emphasised the use of the possessive pronoun, “our”, in the above paragraph because the use of the possessive pronoun by White Rhodesians in relation to the African population was quite common. Similarly, the Unbekoming narrative reveals the White Rhodesian attitude to ownership of the country itself. It was theirs and theirs alone, as revealed in this passage from the Unbekoming piece, which seeks to explain the supposedly amazing living standards enjoyed by Black Rhodesians. When he says “Rhodesians” at the start, he is referring to White Rhodesians:

“Rhodesians viewed the country as theirs “in perpetuity” where their children and grandchildren would continue living, unlike British colonial administrators who would return home after short service periods. This long-term mindset supposedly created “the need for us to work in conjunction with our indigenous people and incorporate them into our plans for the future,” resulting in what are called “the best race relations and the highest standard of living for our people than any country in Africa.”” [emphasis added]

How awfully kind of White Rhodesians to work with their indigenous people and incorporate them into their plans! If it is necessary for me to explain why this language is so wretch-inducing, then I’m afraid you are one of them.

The unwillingness to share the land, while regarding the majority of its inhabitants as a property adjunct to the land, is a congenital disease of the settler colonial mind. In the above quote we see an attempt to attribute some sort of permanent quality to the Rhodesian settler, when in fact they were no more permanent than any other “British colonial administrators”. We will learn in subsequent essays that at no time throughout the history of Rhodesia did the White minority of the population born in Rhodesia ever exceed 50% of the total white population. As late as 1969, the percentage of Whites born outside Rhodesia was 59%. In one generation, the European population more than tripled due to post-war emigration from 69,000 to 221,500 between 1941 and 1961[iii]. Roger Howman, a Rhodesian civil servant of 54 years, observed that “the Census of 1956 revealed that less than 15 per cent of white Rhodesians over the age of 20 were born in the country. The great bulk of immigrants – many only moving in after World War II – identified themselves as British.”[iv]

Returning to the claim regarding the living standards of Black Rhodesians, there is an assertion that Black migrants from other countries were flooding into Rhodesia to avail themselves of these ‘opportunities’. There is no pause for thought about the irony of celebrating uncontrolled black immigration between African states, when the same groups of people producing the kind of narrative typified by the Unbekoming piece also tend to strenuously reject immigration from developing countries into the West. There is no questioning of the potential for such immigration to be related to exploitative economic policies to depress the price of labour by over-supply. This policy objective underpinned the freedom-of-movement pillar of EU economic policy from the 1990s onwards, and we will see in Part VI that it was no different in colonial Rhodesia. Workers were not flocking to a land of milk and honey. They were being imported to address shortages and to keep wages down. Crucially, many of these migrants were using Rhodesia as a staging post to get to South Africa where, ironically, the wages were superior to that of Rhodesia, notwithstanding that South Africa had acquired a reputation for being the country with the harshest apartheid policies in Southern Africa.

Turning to the “merit-based” voting franchise, peddlers of this particular component of the myth ride it harder than Roy Rogers rode his stallion Trigger. The reason they push it as if their lives depended on it is because it is a half-truth that amounts to a whole lie, and therefore works extremely well as a propaganda prop. The reality, which is not that difficult to expose if you’re prepared to leave YouTube for more than three hours and re-acquaint yourself with reading well-researched books, is that it was the final nail in the coffin of African advancement that was built on the back of land, income and educational impoverishment.

The qualifications for voting were income, wealth and education, which causes the myth peddlers extolling the virtues of such a system to sheepishly acknowledge that it was “imperfect”. Its design was in fact diabolically perfect because it excluded, as intended, virtually the entire African population from having a meaningful vote. It became so disgraceful and openly racist in the final years of White minority rule, that the system was divided into a “European roll” and an “African roll”, which ensured that 76% of seats in parliament were allocated to White candidates. But, according to the Unbekoming narrative, that’s not racist at all. In fact Unbekoming would have you believe that this was a choice made by ‘the natives’ themselves – they just wanted to be left alone in their Tribal Trust Lands – the name that the settlers gave to the areas where Africans were corralled after they’d taken the best land for themselves. Yes, here’s how the Unbekoming narrative expressed the absence of African participation in voting:

“Most Africans simply didn’t meet the qualifications or even desire to participate in the Western democratic system. “Most Africans simply didn’t want to know” about voting rights, preferring to live in tribal trust lands “just as their ancestors had” under the authority of tribal chiefs.” [emphasis added]

Yet in 1979, when Africans were finally given the chance to vote en masse for a Black party, some 1.2 million voted for the United African National Council (UANC). That election preceded the institution of a rigged ‘internal settlement’ in which a party led by an African leader (Bishop Muzorewa), won a majority of seats, and was backed by the South African apartheid regime as part of South Africa’s strategy to sustain white minority rule, while presenting a façade of majority black-rule transition. Indeed, when leaders across Europe and Africa were canvassed for their opinion on the recognition of the internal settlement of February 1979, the only state that was prepared to back the Muzorewa government was apartheid South Africa itself[v]. The nickname Black Zimbabweans gave to Muzorewa was ‘Blacksmith’: Muzorewa’s cabinet remained dominated by Ian Smith and his fellow members of the reactionary White Rhodesia Front party.

The 1979 election and the short-lived government of Zimbabwe-Rhodesia – itself a hideously contradictory concatenation – was not internationally recognised because the election excluded major political parties from the African nationalist movements who had been at the forefront of the liberation struggle. When those parties were admitted into the equation in 1980, they won a landslide victory, giving birth to the present day Zimbabwe.

So much for Africans simply not “want[ing] to know about voting rights”. As soon as they were allowed to vote, and were given a broader range of choices, they voted for parties they thought would better represent their interests, and those parties weren’t from the White minority who had systematically disenfranchised them since 1890. The settlers had a hunch that this would happen, and this is what they had been desperately trying to avoid since 1890 – “an excess of democracy” in Zimbabwe[vi].

The language of race in discussing a history of Rhodesia, now Zimbabwe

I feel that we should discuss the most commonly used racial labels that inevitably mar the landscape when analysing a topic like the history of colonial rule in Rhodesia. Obviously, ‘race’ was a divide-and-rule tactic used very effectively in the project of grand theft that came to be known historically as colonialism. That does not mean that the racism was not real. The colonial settlers bought into race discrimination lock stock and barrel. Ultimately , discrimination and exploitation along racial lines was the reason why the Black population fought against White minority rule.

It is impossible to have a discussion about colonialism in Africa without reference to ‘race’ and skin colour. The entire premise underlying colonialism was racist. The assumption propagated to advance colonialism in Africa was that if people in far-off lands were not technologically advanced enough to defend themselves against European aggression, this weakness implied that they were genetically inferior, that their societies were ‘uncivilised’, and that subjugation by a ‘civilised’ power was not only inevitable but beneficial to those on the sharp end of the equation. These ingrained racist attitudes resulted in racist legislation, and racist language permeated that legislation.

That had a knock-on effect on the whole of society. The people administering the systems had to adhere to the racist structures they were administering, and all people in society were forced to structure their lives accordingly. The whole sordid arrangement could not have worked otherwise. So the idea, as expounded in the Unbekoming piece, that Rhodesian colonialism was not racist is not only beyond childish, it is a perversion of the truth that mocks the victims. Whether this lie is propagated maliciously or ignorantly is a debate that I leave to the reader.

If Rhodesian legislation clearly and persistently distinguished between “Africans”/“natives”, and “Europeans” / “Whites”) – and it did – then a most curious feature of the system was the Imperial Government’s purported concern in overseeing Rhodesian legislation to ensure that it wasn’t discriminatory. They set up a “Native Department” to manage the indigenous inhabitants as a resource and to keep them in check. They made laws allocating land between ‘Africans’ and ‘Europeans’, and even laws that excluded ‘natives’ from the definition of ‘employee’. And yet there was a Colonial Department claiming to protect the interests of the ‘native’. I will get into an explanation of that in the course of the essays, but suffice to say for now that, similar to the claims I am rebutting, the whole system was riddled with contradictions. If it were not so tragic, it would provide endless material for Monty Pythonesque sketches. In fact I think it did.

Therefore, the term ‘African’, when you see it in these articles, will denote Black indigenous Zimbabweans during the colonial period up to 1980, because the historical record and the legislation carried that meaning, and it is the word most commonly used by historians in their writings on the subject. I had a discussion with a White Zimbabwean in London a few years ago and I made the mistake of implying that he was not African. I did not make this mistake because I thought White people can’t be African. I made this mistake because I implied that his name was not easily identifiable as Zimbabwean, and he took this to imply that I had denied him his African identity, which I was not trying to do at all. He took offence, and I understand why. You can be a White African, and I would not deny a person who happens to have white skin their wish to identify as African. But for the purposes of this essay, ‘African’ invariably connotes Black ethnicity because that was the connotation at the time, and all the history books reflect this. Neither Black Zimbabweans (like myself!) nor White Africans should take offence when reading these essays.

It would be wrong for readers to interpret the above paragraph as an endorsement of the idea that one can identify as anything they wish. Suffice to say that the clash between identity and reality is the subject of a whole other essay. I have spent a very good portion of my life thinking about identity and, the older I get, the more I refuse to fall into identity traps. The urge to identify as something or other is a congenital defect of the human condition, and almost no-one is immune to it. Most identity labels bear no correlation to a person’s values, and many labels testify to the complete absence of values. Either way, they almost always signify a desire to be a member of a tribe, but they offer very little information about whether the person can be trusted.

When I use the term ‘Rhodesian’ or ‘White Rhodesian’, it will generally apply to White Rhodesian society as a collective. This therefore includes White Rhodesian colonial settlers or the descendants of Rhodesian colonial settlers. Therefore when I use the term “Rhodesians” without an ethnicity qualifier, I am referring to White Rhodesians. The term ‘European’ is also widely used throughout the essays because that is a term that was used by colonial administrators in creating racial categories, and administering society accordingly. It is therefore a term that historians, in interrogating the historical record, would have had to use.

A brief note on the tendency of labels to lead to generalisations about the groups to which they refer. No society is a monolith, but White Rhodesian society displayed a remarkable degree of unity and conformity to the racial attitudes and political systems that produced White dominance of a small minority (5%) over a majority. There were of course White Rhodesians who resisted segregation and spoke out. A common government response to that dissent was revocation of citizenship and deportation.

The academic community within the University of Rhodesia and across Southern Africa was notable for its anti-White supremacist stance. Claire Palley, Reginald Austin, Ian Phimister (born in Northern Rhodesia but wrote extensively about Southern Rhodesia), Philip R Warhurst, Anthony Hawkins, Roger Riddell, and political activists like Diana Mitchell and Guy Clutton-Brock are just a few names of White Rhodesians, or Europeans with close associations with Southern Africa, I have encountered in my research. Clutton-Brock was the first White man to be declared a national hero by the government of Zimbabwe. He was expelled by the Smith regime in 1971, and his citizenship was revoked after his cooperative Cold Comfort Farm was declared an Unlawful Organisation.

‘Black Rhodesian’ will obviously be used synonymously with Black, or African, citizens of the then Rhodesia. While the vast majority of Black Rhodesians chafed under, and therefore resented, the Rhodesian apartheid system, there were some Black Rhodesians (therefore also “Africans” using colonial racial terminology) whose minds were colonised and helped, for a complex range of reasons, to prop up White minority rule. The corollary of a minority within the White community resisting apartheid is a minority of Africans supporting the racist system. This is not a new or unique phenomenon when examining colonialism, and it is falsely (and idiotically) seized on by Rhodesian sympathisers as justification of the system. It merely shows what has been evident in all systems of oppression since time immemorial – that some people within the oppressed group will side with the colonising force at certain times and in certain situations in order to position themselves more favourably. It does not detract from the criminal nature of the colonising project.

In the final analysis, I regard the term ‘Rhodesian’ as a pejorative, and I may occasionally use it that way. Anyone who uses the label of ‘Rhodesian’ today with a sense of pride is categorically a knave and a fool. If you make it to the end of this series, or even absorb a portion of them, you’ll understand why I hold that view. The term used by Zimbabweans to describe unreconstructed Rhodesians is “Rhodie” and, when we are feeling polite, it is usually preceded by adjectives like stupid, dumb, or thick. I had friendships with White people who may have regarded themselves as Rhodesians before 1980, and who I then assumed had come to regard themselves as Zimbabweans after 1980. If, however, they still nostalgically think of themselves as ‘Rhodesian’, then I’m afraid I was sorely mistaken about our friendship.

Comments are closed.